Stay informed with free updates

Simply sign up to the Artificial intelligence myFT Digest — delivered directly to your inbox.

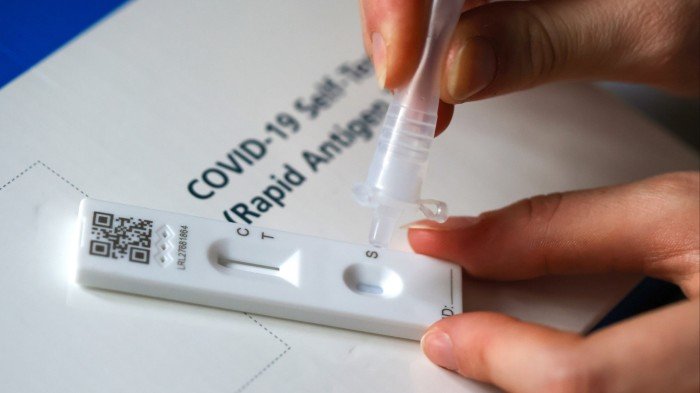

One of my relatives heard some strange stories when working on a healthcare helpline during the Covid pandemic. Her job was to help callers complete the rapid lateral flow tests used millions of times during lockdown. But some callers were clearly confused by the procedure. “So, I’ve drunk the fluid in the tube. What do I do now?” asked one.

That user confusion may be an extreme example of a common technological problem: how ordinary people use a product or service in the real world may diverge wildly from the designers’ intentions in the lab.

Sometimes that misuse can be deliberate, for better or worse. For example, the campaigning organisation Reporters Without Borders has tried to protect free speech in several authoritarian countries by hiding banned content on the Minecraft video game server. Criminals, meanwhile, have been using home 3D printers to manufacture untraceable guns. More often, though, misuse is unintentional, as with the Covid tests. Call it the inadvertent misuse problem, or “imp” for short. The new gremlins in the machines might well be the imps in the chatbots.

Take the general purpose chatbots, such as ChatGPT, that are being used by 17 per cent of Americans at least once a month to self-diagnose health concerns. These chatbots have amazing technological capabilities that would have seemed like magic a few years ago. In terms of clinical knowledge, triage, text summarisation and responses to patient questions, the best models can now match human doctors, according to various tests. Two years ago, for example, a mother in Britain successfully used ChatGPT to identify tethered cord syndrome (related to spina bifida) in her son that had been missed by 17 doctors.

That raises the prospect that these chatbots could one day become the new “front door” to healthcare delivery, improving access at lower cost. This week, Wes Streeting, the UK’s health minister, promised to upgrade the NHS app using artificial intelligence to provide a “doctor in your pocket to guide you through your care”. But the ways in which they can best be used are not the same as how they are most commonly used. A recent study led by the Oxford Internet Institute has highlighted some troubling flaws, with users struggling to use them effectively.

The researchers enrolled 1,298 participants in a randomised, controlled trial to test how well they could use chatbots to respond to 10 medical scenarios, including acute headaches, broken bones and pneumonia. The participants were asked to identify the health condition and find a recommended course of action. Three chatbots were used: OpenAI’s GPT-4o, Meta’s Llama 3 and Cohere’s Command R+, which all have slightly different characteristics.

When the test scenarios were entered directly into the AI models, the chatbots correctly identified the conditions in 94.9 per cent of cases. However, the participants did far worse: they provided incomplete information and the chatbots often misinterpreted their prompts, resulting in the success rate dropping to just 34.5 per cent. The technological capabilities of these models did not change but the human inputs did, leading to very different outputs. What’s worse, the test participants were also outperformed by a control group, who had no access to chatbots but consulted regular search engines instead.

The results of such studies do not mean we should stop using chatbots for health advice. But it does suggest that designers should pay far more attention to how ordinary people might use their services. “Engineers tend to think that people use the technology wrongly. Any user malfunction is therefore the user’s fault. But thinking about a user’s technological skills is fundamental to design,” one AI company founder tells me. That is particularly true with users seeking medical advice, many of whom may be desperate, sick or elderly people showing signs of mental deterioration.

More specialist healthcare chatbots may help. However, a recent Stanford University study found that some widely used therapy chatbots, helping address mental health challenges, can also “introduce biases and failures that could result in dangerous consequences”. Researchers suggest that more guardrails should be included to refine user prompts, proactively request information to guide the interaction and communicate more clearly.

Tech companies and healthcare providers should also do far more user testing in real-world conditions to ensure their models are used appropriately. Developing powerful technologies is one thing; learning how to deploy them effectively is quite another. Beware the imps.

john.thornhill@ft.com