India’s biggest homegrown alternative investment manager is pushing beyond real estate and distressed assets into private credit, hoping to get ahead of a wave of investment from private capital and pension funds in the fast-growing economy.

Mumbai-based Kotak is the biggest Indian player in the country’s nascent alternative asset management industry. Having made its name in real estate funds, it now sees some of the best opportunities in lending directly to companies.

“The nature of opportunities now is going to be more M&A, growth-oriented financing,” said Srini Sriniwasan, managing director of Kotak Investment Advisors, an arm of Kotak Mahindra Bank that manages $8.8bn in assets.

Sriniwasan added that there are also significant opportunities in buying Indian commercial real estate. While “the rest of the world finds office and retail unattractive,” he said, “India is the exact opposite.”

Alternate investments include a broad spectrum of assets including private equity, private debt, infrastructure, real estate, venture capital, growth capital and natural resources.

As demand for distressed assets increases in India, Sriniwasan said that alternative asset managers can also find opportunities in acquisition financing, an area where Indian banks and insurers are not active.

Sriniwasan said that Kotak’s second distressed asset fund, with investment from Singapore and Abu Dhabi sovereign wealth funds GIC and ADIA, has secured $1.25bn, but is targeting $1.6bn in total. The company’s first distressed asset fund, launched in 2019, made a 20 per cent return since launch.

Kotak has also raised a $500mn fund devoted to investing in data centres, which it hopes will make a 25 per cent return, but has put plans to raise a start-up fund on hold because of market volatility and plunging valuations for technology companies.

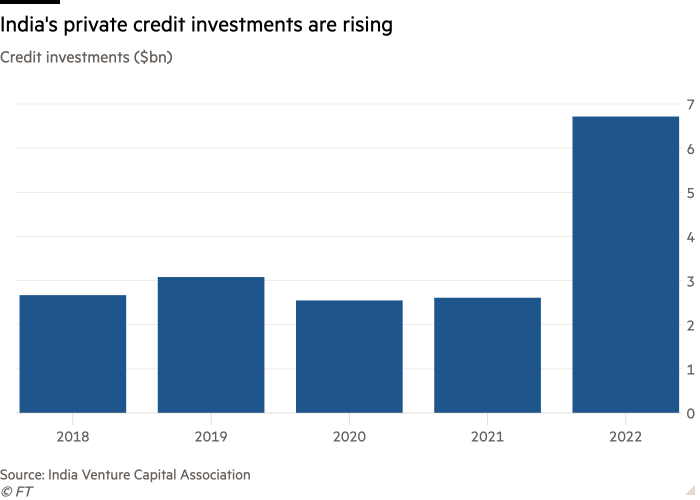

Within India’s alternate asset management sector, “private credit has seen the biggest jump”, said Rajat Tandon, president of the Indian Venture and Alternate Capital Association.

“For investors, equity valuations have fallen, and for companies, the cost of borrowing from banks has got extremely high. Private credit is a good middle of the road for both.

“And in India specifically, traditional lenders are wary after various bad loan shocks, and non-banking finance institutions are still recovering from their liquidity crisis,” Tandon added. “So private credit guys are seizing this opportunity to capture that gap.”

Sriniwasan’s comments come as global groups are pushing into India. Canada Pension Plan Investment Board opened its Mumbai office in 2015. Its most recent bets in India include a $205mn investment in industrial property and warehousing developer IndoSpace’s newest real estate fund.

Meanwhile, global investor Brookfield has recently ploughed more than $1bn into Indian renewable energy group Avaada to finance its green hydrogen and green ammonia ventures.

In 2022, private credit investments represented 12 per cent of India’s $56bn total private equity and venture capital investments, up from 3 per cent in 2021, according to Ernst & Young data presented by IVCA.

Kotak’s growth comes after a series of foreign companies wound up distressed asset funds in the country.

“When we raised the first [special situations] fund [in 2019] Apollo was actually packing up their special situations fund,” said Sriniwasan. “Lone Star was shutting down. And WL Ross had just packed off a couple of years before that.”

Some of the companies “were too early in the game”, said Sriniwasan, adding that the benefits of India’s 2016 bankruptcy code took time to emerge.

The new legal framework allowed creditors to trigger insolvency proceedings against defaulting companies and for courts to overthrow company boards, paving the way for distressed asset sales.

“To be successful in India you have to have feet on the ground,” Sriniwasan added. “This is not a market that you try and operate through what I call suitcase bankers coming out of Hong Kong and Singapore. It may be a nice lifestyle for them, but it’s not going to generate returns.”