Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

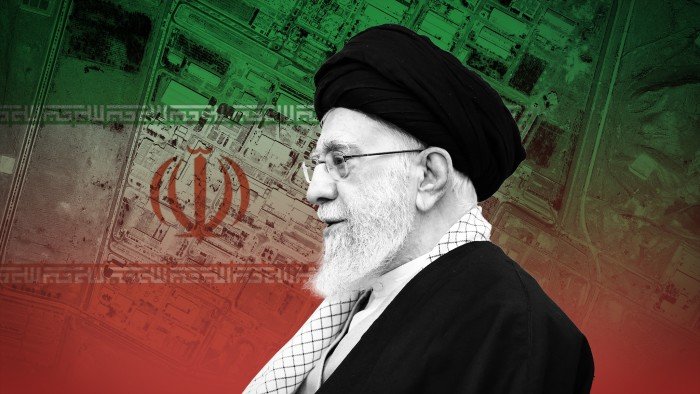

The writer was White House co-ordinator for arms control from 2009-13. He is currently director of the Crown Center for Middle East Studies at Brandeis University

After 12 days of war, US President Donald Trump declared on Tuesday that Iran “will never rebuild” its nuclear programme. But if the recent ceasefire holds and leads to further negotiations over the country’s nuclear future, Iran is unlikely to formally give up its “right” to enrichment, although it may be willing to accept limits. This could include accounting for remaining nuclear materials and equipment, enhanced inspections and limits on Iran’s “peaceful” nuclear activities.

However, US and Israeli attacks on Iran’s nuclear facilities could also drive Iran to withdraw from the non-proliferation treaty (NPT) and “race” to acquire nuclear weapons. It is a logical conclusion for a country that has suffered from massive surprise attacks and needs a credible deterrent against enemies with superior conventional forces. Assuming Iran’s regime survives this war, it will face difficult decisions about whether and how to resume its long nuclear quest.

Iran’s strategy of gradually developing the capability to produce weapons grade nuclear materials under the guise of a peaceful nuclear programme, while delaying a decision to build actual weapons, has been a spectacular failure. Instead of deterring military attacks, it has invited them. An alternative strategy of seeking nuclear weapons without legal constraints, is laden with technical obstacles and security risks. It’s unclear which path Iran will now take. The country’s underlying ability to acquire nuclear weapons will survive the events of the past 12 days. Eliminating some top scientists cannot wipe out the technical knowledge of its many nuclear experts, engineers, and workers. Iran has the basic scientific and industrial infrastructure to rebuild its nuclear programme if it makes a long-term political commitment to do so.

Iran’s physical nuclear infrastructure has suffered grievous damage but it still possesses a large quantity of enriched uranium. According to the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), this stockpile contains roughly 5,000kg of low enriched uranium and 400kg of 60 per cent enriched uranium — which could be converted into enough weapons grade 90 per cent enriched uranium for about 10 nuclear weapons if enriched further. Much of this stockpile has likely been moved to undisclosed locations, along with some equipment that Iran apparently evacuated from Fordow before the US bombs fell.

But it appears that the key enrichment facilities in Natanz and Fordow, and the related site in Isfahan, are no longer operational. Iran is unlikely to try to rebuild them because they will be closely scrutinised and subject to renewed attacks. Instead, it is more likely to build a new enrichment facility in secret, using salvaged components and whatever spare centrifuges it has been able to hide from the IAEA. Producing new advanced centrifuges will be hard because Israel has destroyed the known production facilities, which contain specialised equipment. Despite the bluster of Dmitry Medvedev, deputy chair of Russia’s security council, neither Russia nor anywhere else is likely to provide nuclear warheads to Iran.

Under the NPT, Iran has the right to withdraw three months after giving notice to all parties and the UN Security Council. (North Korea is the only other country to exercise this right.) For Iran, the advantage of withdrawal is that it would no longer be subject to international inspections, meaning it could pursue nuclear weapons with greater secrecy and less vulnerability to future sabotage and military attack. As a practical matter, however, Iran appears to be so penetrated by foreign spies that the absence of IAEA inspections may not provide much additional protection from exposure and detection.

There are other disadvantages to leaving the NPT. Iran’s withdrawal would be seen as a declaration of intent to acquire nuclear weapons and strongly opposed internationally, perhaps even by countries like Russia and China that have criticised US and Israeli attacks on Iran. Outside the NPT, Iran would be more vulnerable to sanctions and export controls that would limit its ability to acquire materials and equipment necessary to rebuild its nuclear programme. It would also be easier for the US and Israel to justify future use of force.

Given these risks, Iran might be better off remaining within the NPT and seeking a purely peaceful nuclear energy capacity under international inspection. But, as this war has shown, such an approach is no guarantee against future attacks on ostensibly peaceful enrichment facilities.