I had landed my first journalism job and was living in a basement studio. I was dating Ron, a fellow Columbia Journalism School grad, and we were scraping by on entry-level salaries. It was 2006, and we were happy exploring the boroughs of New York City together.

Then, one evening, Ron called me and said that his financial situation was untenable, but he had been offered a new job in Taipei. He planned to leave in a month. He wanted to marry me and hoped I would move there, too.

I was stunned by his de facto proposal and spent the next week ruminating. Ron wasn’t a Taiwanese American like me. His family came to America from what is now the Czech Republic, Great Britain, and Ireland, but he had spent more time in Taiwan than I ever had.

After studying international relations at Georgetown, Ron moved to Taiwan for postgraduate Mandarin studies before starting as a journalist. Meanwhile, I had not been to Taiwan since I was 11, when my parents took my brother and me for a family reunion.

I kept thinking about how poor my Mandarin was. Ron was fluent, but I could barely string together a sentence. Unlike a lot of my friends, my parents had not forced us to speak Mandarin at home. I once asked why, and they explained that when they immigrated in the 1970s, they never imagined Mandarin would be considered desirable to learn.

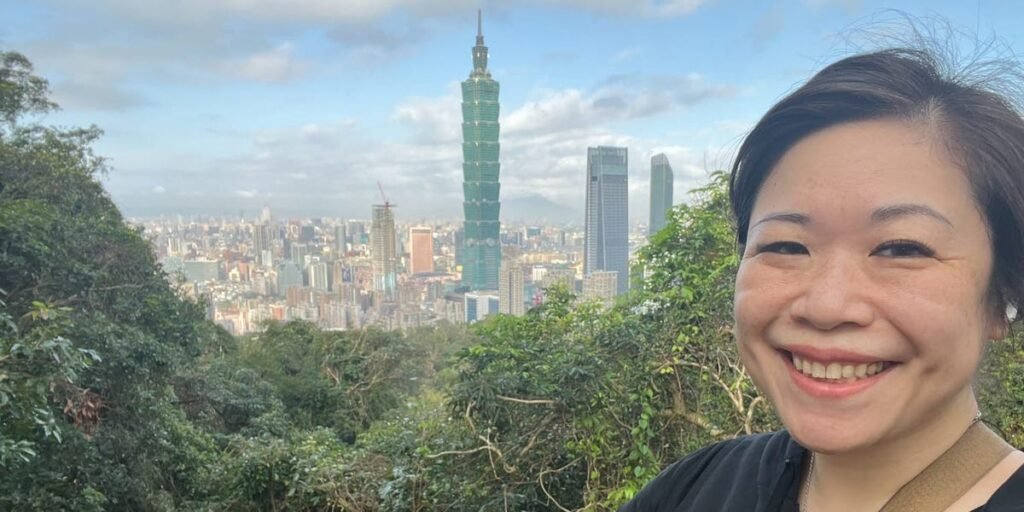

Catherine Shu

Reverse culture shock

For the most part, I wasn’t bothered by my Mandarin, or lack thereof.

I was the first person in my family to be born in the US, and I grew up in a Taiwanese American community about an hour south of San Francisco. Almost all my relatives and parents’ friends spoke English. I thought of myself as American, but there were times when I felt sad to be missing the Taiwanese part.

After the talk with Ron, I began to imagine myself talking in entire Mandarin sentences. I applied for a language scholarship from the Taiwanese government. I called my parents and told them that I was choosing to leave my job at The Wall Street Journal to follow my boyfriend to the city they had left 25 years ago to build their careers as architects in the US.

They were shocked.

I assured them that becoming fluent in Mandarin would not only open up many new journalism opportunities but also help me be closer to our family’s culture.

Armed with my scholarship, I moved in August 2007.

I was eager to embrace Taiwan, but I was immediately hit by culture shock. In New York City, I had been quite talkative, even with strangers, but in Taipei I felt bashful as my fragmented, heavily-accented Mandarin was picked apart.

It soon became clear that looking like I could speak Mandarin, but barely being able to speak, made me an object of ridicule.

I bristled when people asked how my parents forgot to teach me Mandarin. I wanted to tell them: “They did the best to navigate our lives as an immigrant household in the United States,” but I didn’t have the Mandarin to say that. Despite my intensive language studies, I felt like I was living on mute.

Learning how to belong

But I was also learning about my family, just as I’d hoped.

I found out that my neighbor in Taipei had been my grandmother’s classmate in elementary school. After the discovery, the neighbor began treating me like her own granddaughter. She invited me over for tea and told me stories about my grandparents.

The low cost of living, affordable public transportation, and National Health Insurance meant that even though Ron and I still made modest salaries, we were able to explore the city while saving more.

I felt safe even walking around at midnight by myself, giving me a sense of freedom I had never felt before.

Ron and I got married in San Francisco, but held a wedding banquet at Taipei’s landmark Grand Hotel.

Catherine Shu

As my language skills improved, so did my confidence. I got a job at the Taipei Times, where most of my interviews were done in Mandarin, before I started covering Asian startup ecosystems for TechCrunch.

I was worried about having a baby because of chronic health issues, but Ron and I were reassured by Taiwan’s subsidized healthcare. Our daughter was born in 2016, and I spent my customary month of confinement resting in a postpartum maternity center. I have felt immense pride as I watched her grow up equally confident in Mandarin and English.

This August will mark 18 years since I moved here. People often ask us when we’ll move back. “Do you want to move closer to your family? Do you worry about the geopolitical situation? Do you miss America?”

Of course, I tell them. But I think of the clean parks and hiking trails 20 minutes from downtown. I think of living in the neighborhoods where my parents and grandparents grew up. Most of all, I think about how I’ve spent most of my adult life here.

I will always think of the US as home. I am culturally American and still have a heavy accent when I speak Mandarin. Even though I hold dual citizenship, I feel disingenuous when I tell people I’m Taiwanese.

But I know I belong in Taipei.