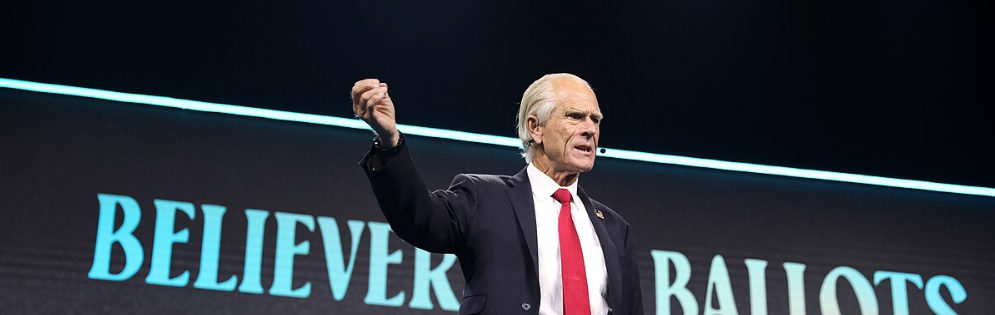

Within the Trump administration there is a vigorous debate between two camps. One group, headed by Peter Navarro, might be called the “true believers”. They favor mercantilist economic policies of the sort that Argentina implemented during the 1940s and 1950s. Another group, headed by Elon Musk, might be called the free traders. In the middle are people like Scott Bessent and Howard Lutnick.

Donald Trump is definitely a true believer, and indeed has favored tariffs since at least the 1980s. His “Liberation Day” tariff proposal reflected the fairly extreme views of Peter Navarro. When the negative market reaction created fears of an economic crisis, Bessent and Lutnick went to Trump and encouraged him to delay the “reciprocal tariffs” (which have nothing to do with reciprocity) by 90 days.

Meanwhile, the debate continues to rage within the Trump administration:

Billionaire presidential adviser Elon Musk attacked White House trade counselor Peter Navarro as “dumber than a sack of bricks” as a fight over President Donald Trump’s tariff regime spilled onto social media on Tuesday.

Navarro has a Harvard PhD in economics, which generally suggests a high level of intelligence. In 1984, Navarro wrote a book mocking the views of protectionists. But then something happened. By 2016, he was making some extremely odd claims. This is from a post I wrote in December 2016:

Navarro and Ross are making the EC101 mistake of drawing causal implications from the famous GDP identity:

GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

Students often assume that trade deficits subtract from GDP, because there is a minus sign attached to imports. What they forget is that the goods imported then show up as a positive in either the consumption of investment category. Navarro also seems to have forgotten this fact.

Elsewhere, Navarro made a number of other elementary errors in economic reasoning. He even made up imaginary experts to buttress his case. In 2024, he served 4 months in prison. Today he is the architect of perhaps the most disruptive policy initiative of the 21st century.

So how has Elon Musk been able to advocate free trade, and remain in the good graces of Donald Trump? Musk is quite clever. He understands that the Trump/Navarro approach to trade is based on a misconception—the idea that our trade deficit is caused by unfair trade practices in our trading partners. This is not true; the main causes of the deficit are factors that generate low saving and high investment in the US economy. But that myth provided an opening for Musk. If it really were true that unfair trade practices were the problem, then a reasonable solution would be negotiations where both sides reduced their trade barriers:

“At the end of the day, I hope it’s agreed that both Europe and the United States should move ideally, in my view, to a zero tariff situation, effectively creating a free trade zone between Europe and North America,” the tech billionaire [Musk] told Matteo Salvini, the leader of Italy’s right-wing League Party.

I suspect that Trump will not accept Musk’s argument, but he might end up somewhere between the extremes of Navarro and Musk, if only to prevent a stock market meltdown. Time will tell.

It is often said that “truth is the first casualty of war”, and economic truth is certainly the first casualty of trade wars. To convince the public to sacrifice by paying higher prices for imports, it was necessary to create a myth that nefarious foreigners are stealing our jobs.

In my December 2016 post, I added this postscript:

PS. It’s not at all clear that Navarro’s ideas will actually be implemented. Some people believe that Trump is more likely to govern as a traditional Republican. The next four years will provide a test of the “Great Man” theory of history. I’m in the camp that believes presidents are far less consequential than most people assume.

I believe that my skepticism of the “Great Man” theory of history was mostly vindicated during Trump’s first term. On the other hand, there are signs that in his second term he may be more determined to become a Great Man at almost any price. So perhaps in the long run I’ll end up being wrong.

(Let’s hope it’s Austerlitz, not Waterloo.)