Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

When, in 1962, Sybil Shainwald applied for a place at Columbia University’s law school she was roundly rebuffed.

The dean said that admitting her would deprive a young man, who might have a 40-year career ahead of him, even though she was already undertaking a doctorate in history at the university and the two departments operated a joint PhD/JD programme.

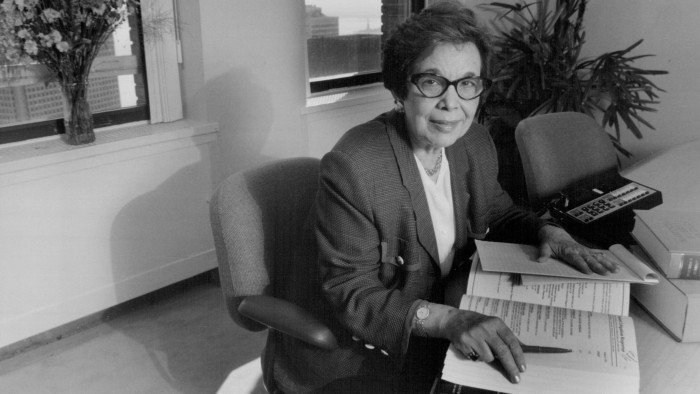

In fact, after finally graduating in law in her late forties, Shainwald, who has died just short of her 97th birthday, bested most of the men admitted in her stead in both longevity and impact, scoring a string of landmark victories over pharmaceutical companies on behalf of women who had been irreparably damaged by ill-tested drugs and devices.

As Shainwald drily put it in an interview with Veteran Feminists of America to mark her 90th birthday: “Luckily, I’ve been practising for more than 40 years.”

Anthony Crowell, dean of New York Law School which gave her the welcome she had been denied at Columbia and where she became a long-serving trustee, said right up to the final weeks of her life, “she was still getting calls from potential clients”.

Raised in Brooklyn in 1928, Sybil Schwartz, as she was then, moved to Virginia at the age of 16 to attend college at William & Mary. The choice of an institution in a state so culturally dissonant with her home borough signalled a willingness to forge her own path that characterised the rest of her life, suggests Crowell: “She was somebody who understood how to very carefully but very, very successfully step out of bounds . . . and to shape a world that she could have great influence and success in.”

After college she combined marriage and raising four children with a career, teaching in public schools and then working in the consumer movement. But after gaining her law degree through evening study at 48 — one of just seven women in a 169-strong class — she struggled to find a niche and had to join a firm unpaid. “I asked if I could take space at a law firm that had only hired men. They said ‘yes, we don’t usually do that, but we’ll do it for you’. And, of course, they called me sweetheart,” she recalled.

A determination to challenge this power imbalance found expression in her work defending women harmed by the pharmaceutical industry. Shainwald believed it had frequently acted without any regard for safety, particularly in relation to contraceptive implants and devices. “We pay with our tax dollars for the research and with our lives for the results,” she told her interviewer.

One battle concerned the Dalkon Shield, a cheap intrauterine device claimed to prevent pregnancy in women too “forgetful” to take the pill. In a speech in 2016, she said: “Nine months after marketing the device, the company first began a two-year baboon safety study. One in every eight baboons died, and 30 per cent suffered uterine perforation. The results were never made public.”

Her most significant triumphs concerned DES, a drug given to pregnant women to prevent miscarriage which turned out to be a carcinogen. She won a groundbreaking case against Eli Lilly on behalf of Joyce Bichler, who at the age of 17 had developed clear cell adenocarcinoma of the vagina and had to have all her reproductive organs and most of her sex organs removed. Her mother had taken the drug.

The men in her firm had been reluctant to take the case to trial, she recalled. It had “turned out to be the most important and pivotal case in the women’s health movement. It brought to light the callous nature of the pharmaceutical industry and is the most egregious example of the industry’s treatment of women”.

Her advocacy, pursued over many years, on behalf of DES victims led to one of the achievements that she was most proud of: overturning in New York state a law that said under-21s could not bring cases. She was also instrumental in expanding the statute of limitations for women’s health cases in New York.

Shanna Swan, a reproductive epidemiologist who acted as an expert witness in some of the cases she brought and became a close friend, said Shainwald was, first and foremost “a very ardent, passionate feminist”. This even extended to the art she amassed. “She always collected only art by women and of women,” Swan said.

Despite the bitter battles she waged with the pharma industry over decades, Swan said she did not believe Shainwald ever felt daunted or afraid: “I don’t think much threatened Sybil, honestly — she was really tough. And she knew she was right.”