Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Swiss pharmaceutical company Roche is planning to move a new antibiotic into late stage clinical trials after early studies showed it had potential to tackle a common superbug that has become resistant to other treatments.

If successful, it would be the first new class of antibiotic capable of killing acinetobacter or any other “Gram-negative” bacteria to be developed for more than 50 years. This type of bug has a structure that makes it more difficult to treat.

Roche will launch a phase 3 trial for zosurabalpin at the end of the year, or early next year. Acinetobacter can cause life-threatening infections including pneumonia and sepsis. Patients who are immunocompromised because of cancer or other serious diseases are particularly vulnerable.

Larry Tsai, global head of immunology and product development at Genentech, a unit of Roche, and a pulmonary critical care physician, estimates that 40 to 60 per cent of acinetobacter infected patients die as a result of the bug.

The trial will recruit about 400 patients at more than 100 sites worldwide, with the aim of getting the drug approved towards the end of the decade.

Tsai said Roche was continuing its long legacy of developing new antibiotics “to ensure they are available as part of what we see as our societal commitment to global health security”.

After a period when it withdrew from the field, about ten years ago Roche reinvested in tackling the growing problem of antimicrobial resistance, which the World Health Organization estimates could kill 10mn people a year by 2050.

Many drugmakers are reluctant to pursue new antibiotics because of a difficult market: the drugs are now used much more sparingly to try to prevent bacteria from building up resistance, meaning it can be hard to sell enough to cover the cost of research and development.

Many smaller companies focused on developing antibiotics have struggled and some have closed. Tsai said that he understood the challenges first hand, having worked at a company with a promising antibiotic that still shut down.

But he said there was increasing global recognition that antimicrobial resistance has been “neglected over the past few decades” and that health systems were attempting to change the incentives.

Policymakers have been searching for ways to encourage antibiotic development. The UK has adopted a model where drugmakers are paid an annual fee for making the medicines available, rather than for the volume used, while the US Congress has been discussing a similar model.

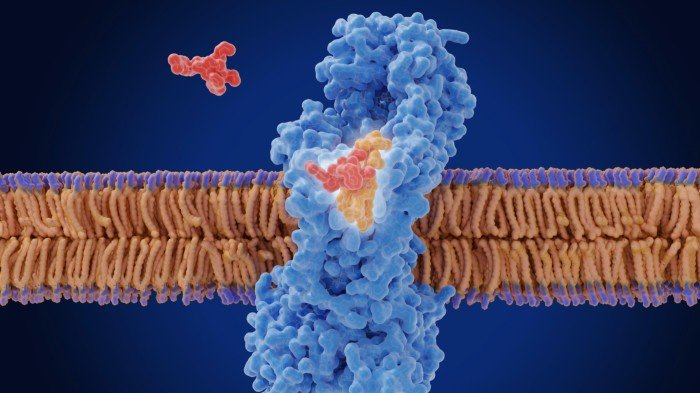

Gram-negative bacteria are particularly hard to treat because they have a second outer membrane, creating a formidable barrier for drugs to cross. The last new class of antibiotics approved to treat Gram-negative bacteria was in 1968.

Roche worked with researchers at Harvard to find a new way to kill the bacteria, weakening the cell’s membrane by inhibiting a key component — a chemical called lipopolysaccharide — that boosts the membrane’s resilience.

Michael Lobritz, global head of infectious diseases at Roche Pharma research and early development, said looking for new classes of antibiotics involved “going back to the drawing board” and examining how bacteria work. Scientists can then build on new discoveries and potentially find other new antibiotics.

“This antibiotic is important, but it can also serve as a catalysis point for future innovation. Finding new classes is very hard. There are very few . . . that have been discovered in the last 15 years. So if you are able to launch a new one, we can build off that for decades to come,” he said.